I’ve had a few customers ask for information on how to detect account expirations in Active Directory. There are a number of ways to do it, but one of the more interesting ways is to compute the expiration based on the accountExpires attribute.

You can use this “handy” one-liner (I promise–it is all one line):

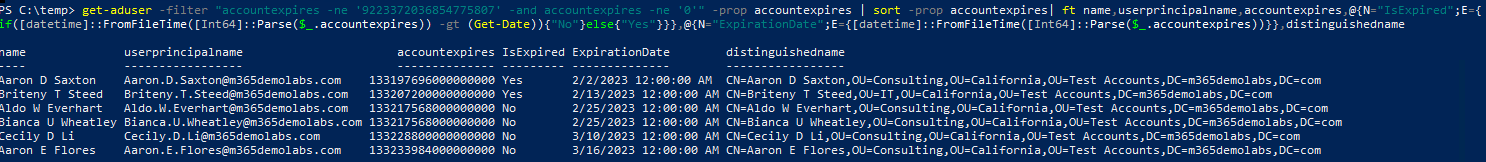

Get-AdUser -Filter "accountExpires -ne '9223372036854775807' -and accountExpires -ne '0'" -prop accountExpires | Sort -Property accountExpires | FT Name,UserPrincipalName,accountExpires,@{N="IsExpired";E={If([datetime]::FromFileTime([Int64]::Parse($_.accountexpires)) -gt (Get-Date)){"No"}Else{"Yes"}}},@{N="ExpirationDate";E={[datetime]::FromFileTime([Int64]::Parse($_.accountExpires))}},DistinguishedName

When you run it, it will output a table that you can use to examine accounts.

For some history on how this works, you can read my post about disabling expired accounts with AAD Connect. For those of you who don’t want or need the whole experience, I’ve snipped out the relevant tidbits:

The accountExpires property is a large integer which stores the date value in FILETIME syntax. And what is FILETIME, you ask?

I’m so glad you did, because now it’s time for a story.

FILETIME is one of the systems of record for describing computing dates. It all starts with a time machine and traveling back to the adopting of the Gregorian calendar in 1582. The calendar, based on a 400-year cycle (called an epoch), “restarted” on January 1, 1601 and ran through December 31, 2000. Windows records time in 100-nanosecond intervals (called ticks) elapsed since the beginning of this epoch. This beginning is sometimes referred to as the zero date.

Modern computing began after the Gregorian calendar was introduced (but before the start of the second epoch), and somewhere along the line, everyone just generally agreed to keep on counting rather than starting over. The accountExpires value is essentially the number of nano-second intervals elapsed since January 1, 1601 12:00:00AM.

Other systems (and even some applications) have different zero dates as a baseline, but are generally counted the same. For example:

- The UUID epoch in RFC4122 starts October 15, 1582 –the first day Pope Gregory XIII switched the world away from the Julian calendar. The UUID epoch nearly 18 years before the Windows epoch begins (or -5748192000000000 ticks, if you’d rather count that way).

- Microsoft Excel originally used December 30, 1899 as its zero day. Because of a bug with Lotus 1-2-3 incorrectly calculating 1900 as a leap year, Microsoft chose to use the same incorrect calculation as Lotus to ensure cross-application workbook compatibility.

- Microsoft later changed the official zero date to January 1, 1900.

- Interestingly, Microsoft Excel also recognizes a zero date of January 1, 1904, due to early compatibility problems with Mac systems.

- Microsoft SQL Server uses January 1, 1900 as its epoch beginning.

- Chrome and Webkit also use January 1, 1601 as their epoch start date, but count in microseconds instead of nanoseconds.

- The Unix epoch starts January 1, 1970. It originally started on January 1, 1971 and was originally counted using 1/60th of a second intervals. The largest number a 32-bit system can represent is (2^31)-1. Later, the Unix epoch counting was revised to 1-second intervals. The 32-bit space for the Unix epoch runs out in on January 19, 2038 at 3:14:08 AM.

If you’ve ever wondered why those numbers pop up periodically in computing, now you know.

As part of a customer issue, I’ve updated the corresponding documentation at Microsoft Learn to reflect this lifecycle of the accountExpires attribute.

- When an account is initially provisioned, the

accountExpiresvalue is set to9223372036854775807, which correlates to the radio button Never on the Account tab of an AD user object’s property sheet under the expiration section. This value isn’t technically a date, as it represents the signed 64-bit integer limit. If it were a date though, using a Unix epoch calculator, this value evaluates to the April 11, 2262 (in nanoseconds) or somewhere in the year 29,228 if you’re using a 64-bit epoch date. In either case, it’s not exactly never, but it’s not a date anyway. - If an account is configured with an expiration date, the original value in

accountExpiresis set to the correspondingFILETIMEvalue of the expiration date. - If an account is later configured to Never expire, instead of reverting back to

9223372036854775807, theaccountExpiresvalue is set to0.

So, when computing the accountExpires value, you need to convert it from its current storage format (FILETIME) to something a little easier to read. PowerShell has a constructor called [datetime], and part of its definition includes a number of methods (functions or actions) that, when used appropriately, allow you to convert all sorts of numeric values to the various types of date values that PowerShell supports:

[datetime]::FromFileTime([Int64]::Parse($_.accountExpires))

In this case, you can read this backwards: Taking an AD user object’s accountExpires value (which is a 64-bit integer), you can tell the system to interpret it as a FILETIME value, and take the well-known understanding of how FILETIME is computed and convert it to a human-readable date.