When attempting to migrate a Microsoft 365 organization from federated authentication to Password Hash Sync, there are a couple of gotchas that can impact how you manage certain accounts. These changes in authentication behavior determine whether you need to implement new workflows or business processes–changes surrounding expired accounts and accounts flagged to force password change on next logon.

This is an updated version of this post: Working around accounts that expire with AAD Connect. This post features a different script and a different rule. The same outcome, but a better (or at least more preferred way) since it’s a better practice to have the MV be the changed values so you can see what’s going to get exported.

Background

With federated identity, authentication is processed via the on-premises identity system–typically an AD FS farm that is connected to Active Directory.

In the first of many sidebars for this post, I want to mention that there are several different federation solutions that work with Azure AD. The other two most common ones are PING (which can be configured and integrated via AAD Connect) and OKTA. PING deployments typically use AAD Connect to synchronize identity directly to Azure AD while OKTA has its own synchronization engine.

Anyway.

When a user attempts to log on to Azure AD via federation, a number of things are evaluated:

- Is the account password correct?

- Is the option to force a password change set?

- Is the account enabled?

- Is the account expired?

When migrating to password hash sync, there are several items that Microsoft identifies as changes in behavior that you need to be aware of.

From the guide:

Password expiration policy

If a user is in the scope of password synchronization, the cloud account password is set to Never Expire. Users can continue to sign in to cloud services by using a synchronized password that is expired in the on-premises environment. The cloud password is updated the next time the password is changed on-premises.

Account expiration

If your organization uses the

accountExpiresattribute as part of user account management, be aware that this attribute is not synchronized to Azure AD. As a result, an expired Active Directory account in an environment configured for password hash synchronization will still be active in Azure AD. We recommend that if the account is expired, a workflow action should trigger a PowerShell script that disables the user’s Azure AD account (use the Set-AzureADUser cmdlet). Conversely, when the account is turned on, the Azure AD instance should be turned on.User must change password at next logon

When the option “User must change password at next logon” is selected for an account, the password is not synchronized to Azure AD. In this case, the user needs to change the password on-premises to allow the new password to be synchronized. This can be done directly on a domain-joined device.

While I can’t address all of the caveats, there are some things we can do.

Account expiration

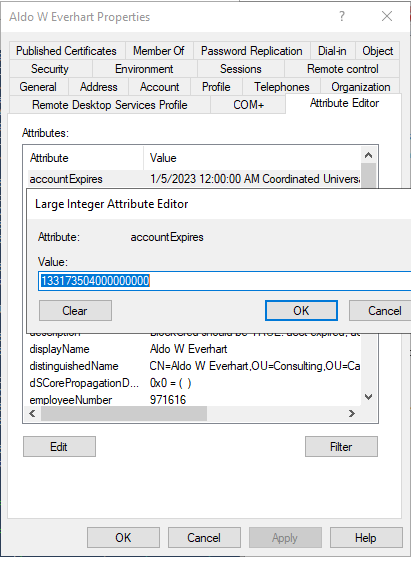

Account expiration is tracked via the accountExpires attribute in Active Directory:

The property is a large integer which stores the date value in FILETIME syntax. And what is FILETIME, you ask?

I’m so glad you did, because now it’s time for a story.

FILETIME is one of the systems of record for describing computing dates. It all starts with a time machine and traveling back to the adopting of the Gregorian calendar in 1582. The calendar, based on a 400-year cycle (called an epoch), “restarted” on January 1, 1601 and ran through December 31, 2000. Windows records time in 100-nanosecond intervals (called ticks) elapsed since the beginning of this epoch. This beginning is sometimes referred to as the zero date.

Modern computing began after the Gregorian calendar was introduced (but before the start of the second epoch), and somewhere along the line, everyone just generally agreed to keep on counting rather than starting over. The accountExpires value is essentially the number of nano-second intervals elapsed since January 1, 1601 12:00:00AM.

Other systems (and even some applications) have different zero dates as a baseline, but are generally counted the same. For example:

- The UUID epoch in RFC4122 starts October 15, 1582 –the first day Pope Gregory XIII switched the world away from the Julian calendar. The UUID epoch nearly 18 years before the Windows epoch begins (or -5748192000000000 ticks, if you’d rather count that way).

- Microsoft Excel originally used December 30, 1899 as its zero day. Because of a bug with Lotus 1-2-3 incorrectly calculating 1900 as a leap year, Microsoft chose to use the same incorrect calculation as Lotus to ensure cross-application workbook compatibility.

- Microsoft later changed the official zero date to January 1, 1900.

- Interestingly, Microsoft Excel also recognizes a zero date of January 1, 1904, due to early compatibility problems with Mac systems.

- Microsoft SQL Server uses January 1, 1900 as its epoch beginning.

- Chrome and Webkit also use January 1, 1601 as their epoch start date, but count in microseconds instead of nanoseconds.

- The Unix epoch starts January 1, 1970. It originally started on January 1, 1971 and was originally counted using 1/60th of a second intervals. The largest number a 32-bit system can represent is (2^31)-1. Later, the Unix epoch counting was revised to 1-second intervals. The 32-bit space for the Unix epoch runs out in on January 19, 2038 at 3:14:08 AM.

If you’ve ever wondered why those numbers pop up periodically in computing, now you know.

There are some interesting things to know about this that I discovered while working with Ric Poplin. (I’ve updated the corresponding documentation at Microsoft Learn to reflect this lifecycle of the accountExpires attribute).

- When an account is initially provisioned, the

accountExpiresvalue is set to9223372036854775807, which correlates to the radio button Never on the Account tab of an AD user object’s property sheet under the expiration section. This value isn’t technically a date, as it represents the signed 64-bit integer limit. If it were a date though, using a Unix epoch calculator, this value evaluates to the April 11, 2262 (in nanoseconds) or somewhere in the year 29,228 if you’re using a 64-bit epoch date. In either case, it’s not exactly never, but it’s not a date anyway. - If an account is configured with an expiration date, the original value in

accountExpiresis set to the corresponding FILETIME value of the expiration date. - If an account is later configured to Never expire, instead of reverting back to

9223372036854775807, theaccountExpiresvalue is set to0.

I digress.

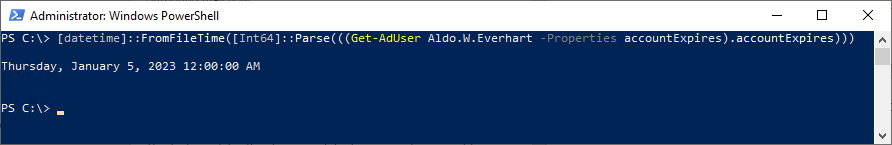

For us normal humans, the well-known Windows epoch format can be converted easily to a [datetime] value.

[datetime]::FromFileTime([Int64]::Parse(((Get-AdUser <sAMAccountName> -Properties accountExpires).accountExpires)))

As a large integer, this is relatively easy to calculate against. When evaluating an account expiration time, we can simply compare it against the current time retrieved during the AAD Connect synchronization task runs using this pseudo-logic:

If accountExpires is greater than (later than) Now, then the account hasn’t expired.

Easy peasy, lemon squeezy.

Force password change on next logon

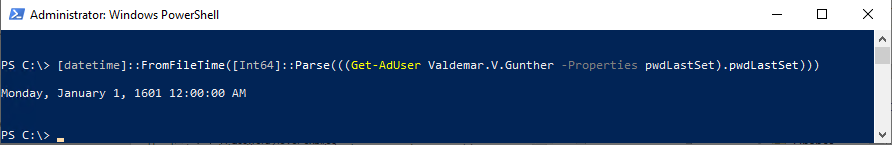

When you select the User must change password at next logon box (either through the Account tab of ADUC or through during the Reset User Password workflow), the on-premises pwdLastSet attribute (also stored a large integer) is reset to January 1, 1601.

[datetime]::FromFileTime([Int64]::Parse(((Get-AdUser <sAMAccountName> -Properties pwdLastSet).pwdLastSet)))

This is easy to detect on-premises with AAD Connect, but we’re really limited in what we can do with that platform. There are a few things we can do:

Cloud disable

Similar to disabling a cloud account for an on-premises account that has expired, we can craft a rule that disables the cloud account when “Force change password” is set on-premises. Not ideal, but it’s a potential in-box solution depending on your organization’s requirements.

Enabling ForcePasswordChangeOnLogOn

The much better option for dealing with forced change passwords is to use a newly supported parameter that flips the bit in Azure to enforce the native password reset authentication flow.

Password expiration

This is the most difficult problem (which is why I saved it for last). There’s nothing in the box that will technically work for it in the exact same way. Back in the olden days, the userAccountControl attribute had a number of flags that you could use to determine the state of an account. You can learn more about the property flags here (https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/ms680832(v=vs.85).aspx) and here (https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/aa772300(v=vs.85).aspx).

However, with modern releases of Windows, this attribute is computed real-time when the user properties are retrieved by evaluating the pwdLastSet timestamp in conjunction with a password policy. This is great to get the up-to-the-minute detail for account properties, but it’s not so great for state-based applications like AAD Connect since they import user and group attributes into a database table and then perform their comparisons and operations on these static values.

I did, however, create a blog post several years ago that presents a method for manually working through this (which involves a series of scheduled scripts and AAD Connect Sync rules). To learn about this solution, go here.

With that being said, let’s get rolling on the first two.

Disabling expired accounts in-cloud

First, we’ll look at fixing the whole account expires thing. This is likely a good business workflow, but you’ll want to get sign-off from the powers that be to ensure that it fits in with your policies.

Updating sync configuration

The heavy lifting will be done with a synchronization rule. This time, however, we’re using an Inbound rule. You’ll need to create an inbound rule for every on-premises directory synchronization source.

Synchronization rules can process data as it’s coming into the MV or as it’s leaving to a connected system. Where you do it depends largely on how many connected directories you’re manipulating objects as well as where you want to see the values reflected–some administrators like to craft rules on import flows so they can see the correct values in the metaverse. In other instances, if you need to apply a standard setting to all objects going to a particular directory, it may be easier to create a single outbound rule. You need to create the rules for each affected data source in whichever direction you’re going.

In this example, I want it to apply to all objects from all source directories (currently two forests) that will be connected to my tenant. My previous example used an outbound rule, but sometimes there can be weirdness trying to view the projected changes. When working with an inbound rule, you get to see the actual data in the MV that you’re working with.

Disabling the sync schedule

Before performing any work on synchronization rules, it’s important to disable the AAD Connect sync schedule. Any time a rule is modified, a full synchronization is scheduled. While that in itself isn’t a bad thing, you don’t want AAD Connect to start processing accounts when you’re in the middle of performing a configuration.

To stop the sync scheduler:

- On the server running AAD Connect, launch an elevated PowerShell prompt.

- Run:

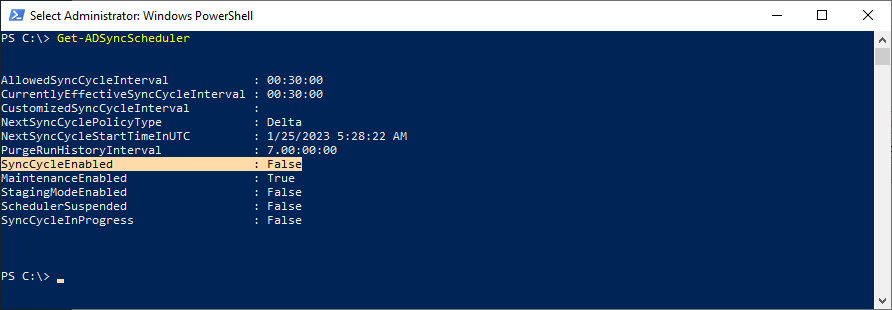

Set-ADSyncScheduler -SyncCycleEnabled $false - Confirm that the schedule is stopped by running

Get-ADSyncScheduler.

Alright. Carry on.

Creating a new rule to disable expired accounts

This process will guide you through creating a rule to disable expired accounts. To do this:

- Launch the Synchronization Rules Editor.

- Under Direction select Inbound and then click Add new rule.

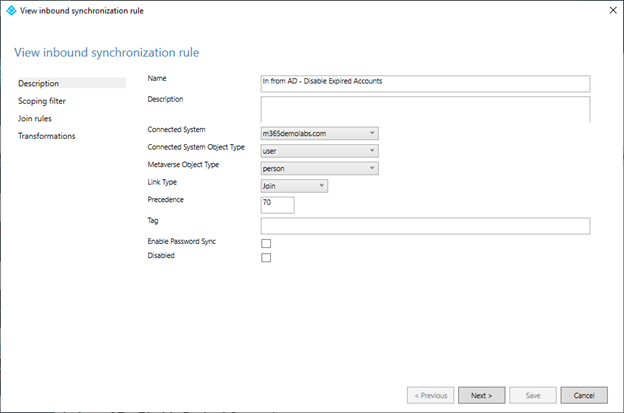

- On the Description page, configure the rule with the following settings:

– Name: In from AD – Disable Expired Account (domain.com)

– Description: [ whatever you’d like ]

– Connected System: [ an on-premises directory ]

– Connected System Object Type: user

– Metaverse Object Type: person

– Link Type: Join

– Precedence: [ whatever you’d like, lower than the lowest current rule. It’s best to leave some space between rule sets in case you need to add new ones later. ]

– Enable Password Sync: [ clear ]

– Disabled: [ clear ]

- Click Next.

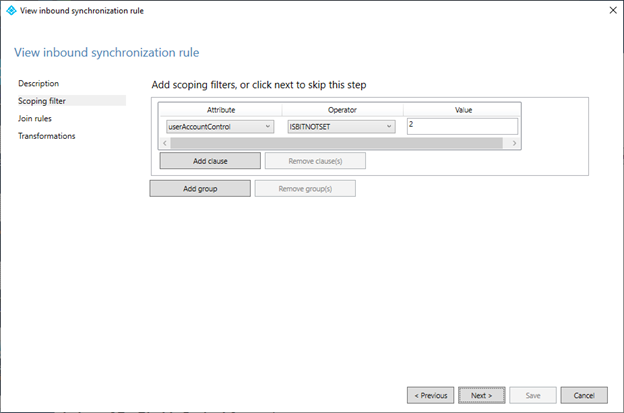

- On the Scoping filter page, click Add clause and configure it with the following values:

– Under Attribute, select userAccountControl.

– Under Operator, select ISBITNOTSET.

– Under Value, enter2. - Review the scoping configuration:

The purpose of this scoping filter is to ensure this rule only operates against accounts that are enabled on-premises. Expired accounts, from AD’s perspective, are still enabled–the directory just denies logon based on the value in theaccountExpiresattribute. Since the rule will be used to disable and enable accounts, we need to make sure we’re not performing activities against objects that have been administratively disabled. - Click Next.

- On the Add join rules page, click Next (without adding any join rules).

- On the Transformations page, click Add transformation and configure it with the following values:

– Flowtype: Expression

– Target Attribute: accountEnabled

– Source:IIF(CStr([accountExpires])="0",True,(IIF(CStr([accountExpires])="9223372036854775807",True,IIF(DateFromNum([accountExpires])>(CDate(NumFromDate(Now()))),True,False))))

– Apply Once: [ clear ]

– Merge Type: Update - Click Save.

When read from left to right, this transform rule performs the following operations:

- Check to see if the value in

accountExpiresis 0. - If it’s zero, then set

accountEnabledtoTRUEand we’re done. If it’s something else, though…Go to step 3. - Check to see if the value in

accountExpiresis9223372036854775807, which doesn’t exactly translate to a real year (it’s instead the maximum value of a 64-bit signed integer). If it were an actual date, it translates to the year 29,228 (probably safe to say it’s way past the expiration date of the human logging in). - If the value is

9223372036854775807, then flow the valueTRUEtoaccountEnabledin Azure AD and we’re done. If the value is something different, go to the next function. - Convert the value from

accountExpiresinto a date and then check to see if it’s greater than the value of the functionNow(which retrieves the current system time at the execution of the synchronization rule). If the value ofaccountExpiresis greater thanNow, then flow the valueTRUEtoaccountEnabledin the metaverse, sinceaccountExpiresis in the future. If the value ofaccountExpiresis less thanNow, then flow the valueFALSEtoaccountEnabledin the metaverse sinceaccountExpiresis in the past.

As always, test. 🙂

Testing

Make a change to a few on-premises accounts test accounts that are in synchronization scope (ideally, these accounts would all be in the same OU so you can easily locate them in the Synchronization Service application).

- Configure account 1 as an AD- enabled account with an account expiration date in the past. Expected result: AAD Connect should flow

FALSEto Azure AD for theaccountEnabledproperty - Configure account 2 as an AD-enabled account with an account expiration date in the future. Expected result: AAD Connect should flow

TRUEto Azure AD for theaccountEnabledproperty. - Configure account 3 as an AD-disabled account. Expected result: AAD Connect should flow

FALSEto Azure AD for theaccountEnabledproperty. - Configure account 4 as an AD-enabled account and set the option for User must change password at next logon. Expected result: AAD Connect should configure the account to prompt for password change when logging in from Azure AD.

- Configure account 5 as an AD-enabled account with an account expiration date in either the past or the future. After saving the object, go back and edit it to set the account expiration radio button to Never expire. Expected result: AAD Connect should flow

TRUEto Azure AD for theaccountEnabledproperty.

You’ll want to make sure that you’ve updated the appropriate property on each account. AAD Connect is stateful and it monitors the directory changes. If you selected accounts that already had those properties, it may be harder to locate them or verify that the new data has been imported into AAD Connect and is being computed properly.

Once that’s done, it’s time to test inside of AAD Connect.

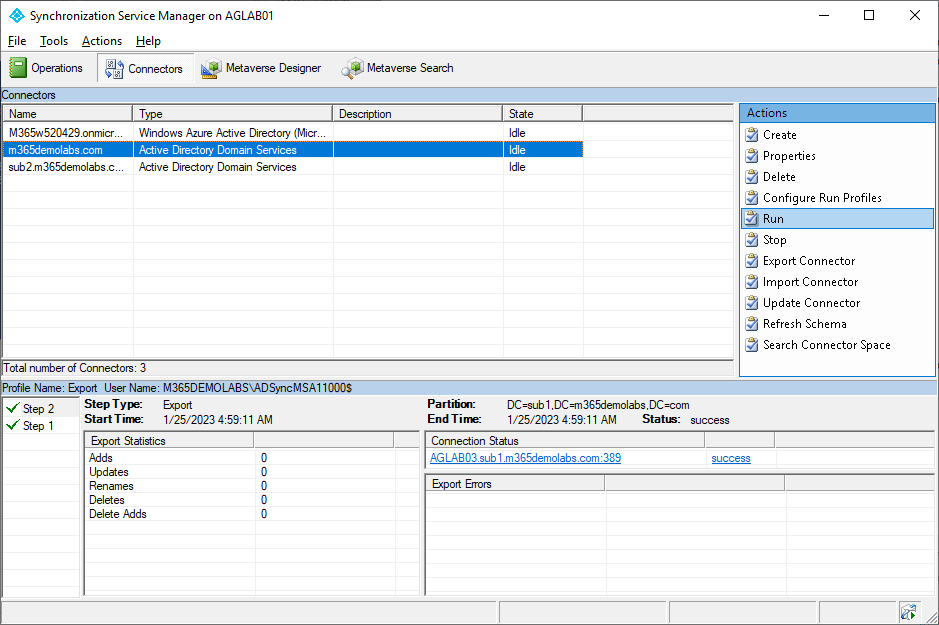

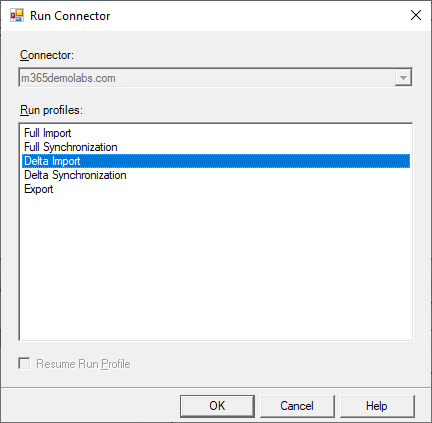

- Launch the Synchronization Service.

- Select the Connectors tab.

- Select the connector that represents the on-premises directory where you made the account updates.

- In the Actions pane, select Run.

- On the Run Connector window, select the Full Import run profile and click OK.

- After the State column has returned to Idle, repeat the process and select Full Synchronization.

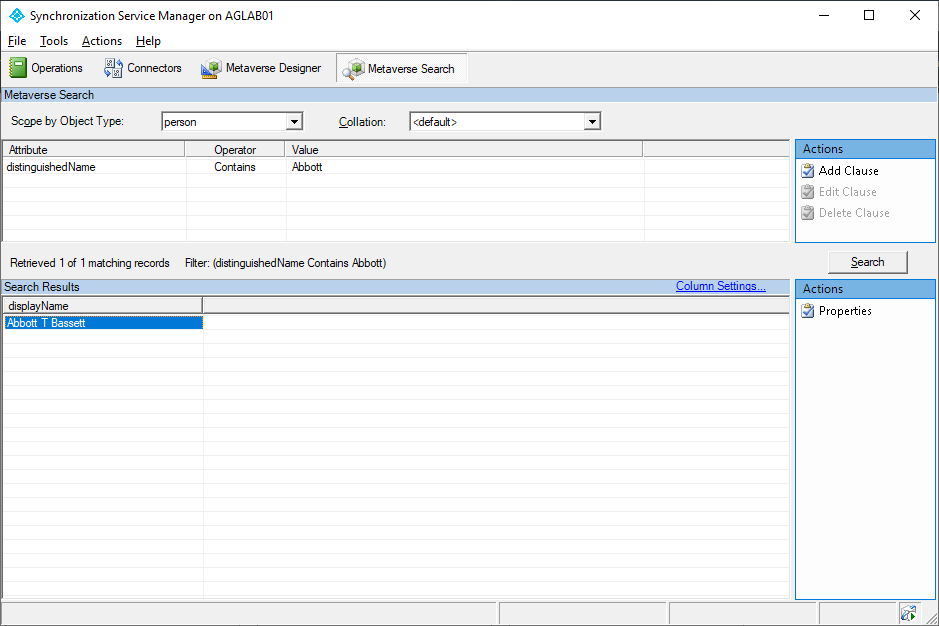

- After the Full Synchronization is done, select the Metaverse Search tab.

- Select the appropriate Scope by Object Type parameter (person).

- Under Actions, select Add Clause and select an attribute that you will use to search for your test user.

- Click Search to search for your test object.

- Select your object from the list and double-click it or select Properties.

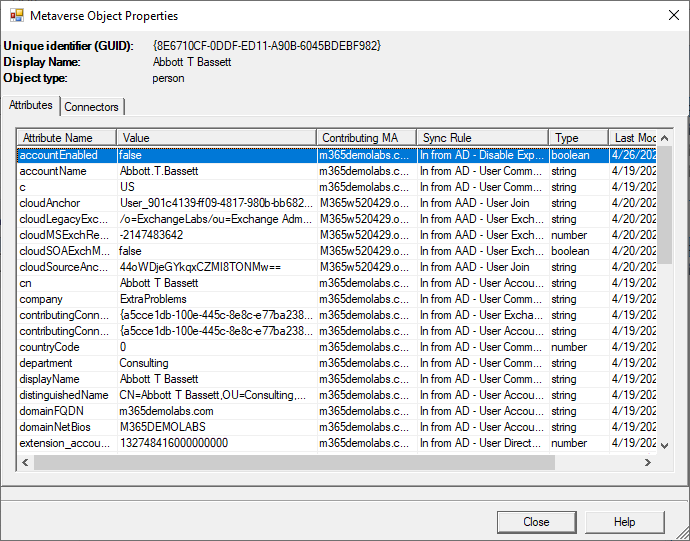

- On the Metaverse Object Properties page, look for the accountEnabled attribute. Compare the value to what it should be based on your object’s expiration date. Verify that the synchronization rule you created earlier is listed in the Sync Rule tab.

- Click Close and repeat for the other test objects.

When you are satisfied that it is working, you can re-enable the scheduler.

Re-enabling the sync scheduler

Enabling the AAD Connect synchronization scheduler is just following the reverse process.

- Launch an elevated PowerShell window.

- Run

Set-ADSyncScheduler -SyncCycleEnabled $true

Since you’ve changed the synchronization rules, AAD Connect will automatically execute the correct import and synchronization tasks on its next run.

That’s it! You’re ready to disable stuff automatically!

BONUS

If you don’t want to configure the rules manually (or want to do it for a lot of AAD Connect deployments), you can use the scripting that I built. You can download the script manually: https://www.powershellgallery.com/packages/New-AADConnectInboundRuleDisableExpiredAccounts or use the Install-Script cmdlet to install it on the AAD Connect server:

Install-Script New-New-AADConnectInboundRuleDisableExpiredAccounts

Then, run the script:

New-AADConnectInboundRuleDisableExpiredAccounts

By default, the script will deploy one sync rule per on-premises Active Directory connector (filtering on the Connector Subtype). If you want to just run it for a single connector (perhaps as a test or if you’ve added more connectors since originally running the script), you can use a few parameters to modify the operation:

.PARAMETER Domain

This option allows you to specify one or more domains (which will be included in the default connector name) to build the rule for.

.PARAMETER CreateTask

This option will create a scheduled Full Synchronization task that will run every other week. Since accountExpires date is not continuously evaluated by AAD Connect, you should schedule periodic full synchronizations on the AD connectors to ensure that all of the accounts get processed in a somewhat timely manner.

Thanks! I think it really has to do, at some level, with limitations of computing power at the time AD was developed.

Account expiration isn’t a flag, per se, but an attribute that indicates a time when the account *will* expire (seconds since January 1, 1601). The accountExpires attribute is checked during the logon process and a quick calculation is done to see if the current data is before or after the accountExpires value. AAD could easily calculate against this as well (but it doesn’t). While functionally, an expired account is similar to a disabled account (in that it can’t log on), it is potentially different as well because of the reasoning.

There’s no timer going in the directory that monitors expired accounts and ‘flips’ a bit to tell the system they’re disabled. Designing a system that way could potentially result in a huge perf hit in a directory with hundreds of thousands or millions of accounts. This way, the evaluation is done at logon time (since it’s only one account and one transaction instead of processing potentially millions of accounts every second).

However, with the scale of compute behind AAD/Entra ID, I don’t see why it can’t be implemented natively.

Fantastic article, Really clear and comprehensive.

Thank you so much.

I really have no idea why this wouldn’t be part of the normal AD connect setup/install as I just can’t think why anyone would set and expire date on the AD for it not to sync to AAD (sorry EntraID!)